How Do Shell Fish Build Their Shells And What Are They Made From?

Seashell Supply on 4th Nov 2025

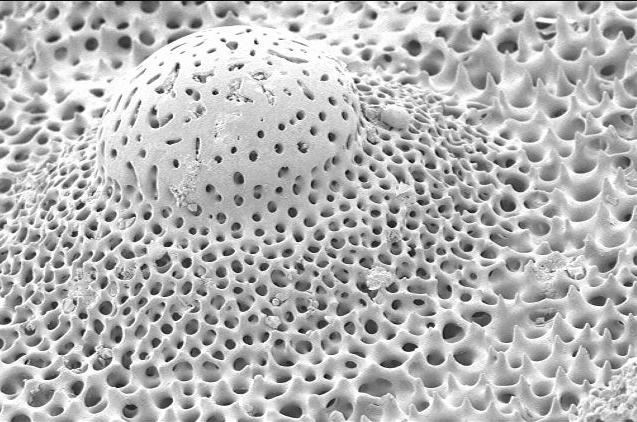

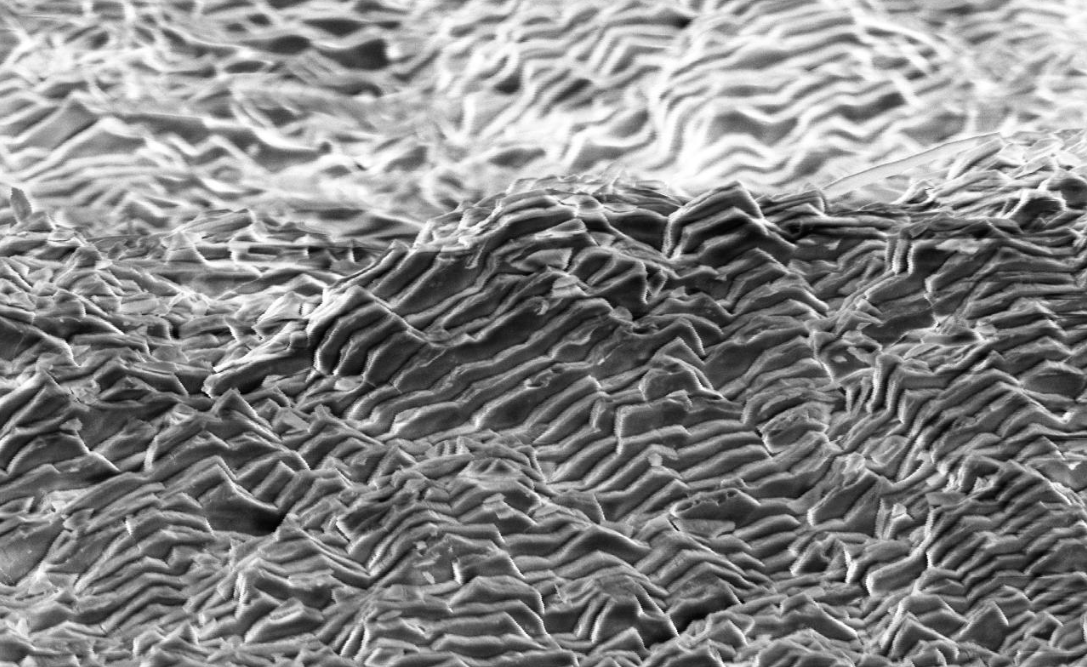

Marine animals build their shells using a specialized tissue called the mantle, which secretes proteins and minerals—primarily calcium carbonate—to form protective, multi-layered structures. These shells are mostly composed of calcite or aragonite crystals, bound together by a protein matrix.

The Science Behind Seashells: How Marine Life Builds Its Armor

From the delicate spirals of a snail to the sturdy plates of a clam, seashells are more than beachcomber treasures—they're biological marvels crafted by marine organisms for protection, structure, and survival. But how exactly do these creatures create such intricate and durable shells? Let’s dive into the fascinating process.

The Mantle: Nature’s Shell Factory

At the heart of shell formation is a specialized tissue called the mantle. Found in mollusks like snails, clams, and oysters, the mantle lines the inside of the shell and acts as a biological workshop. It performs two key functions:

- Secretion of proteins: These proteins form a scaffold or framework that guides the shape and structure of the shell.

- Mineral deposition: The mantle extracts calcium and carbonate ions from seawater and deposits them onto the protein framework as calcium carbonate.

Building Blocks: Calcium Carbonate and Protein

It's amazing how similar the materials that marine life produces to build it's shells are actually very similar to the materials that humans use to build their "shells".... houses and buildings. Their shell materials are very similar to the calcite and sedimentary stone like marble and limestone. Some shells are basically made of cement.

The primary substance in most marine shells is calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), which can crystallize into two forms:

- Calcite: A stable, common crystal found in chalk, limestone, and marble.

- Aragonite: A denser, more fragile form that gives shells their iridescent inner layer, known as nacre or mother-of-pearl.

Shells typically consist of three layers:

|

Layer |

Composition |

Function |

|

Outer layer |

Mostly protein |

Protection from abrasion and predators |

|

Middle layer |

Calcite crystals + protein |

Structural strength |

|

Inner layer |

Aragonite + protein (nacre) |

Smooth surface, sometimes used in pearl formation |

Growth and Adaptation

Shells grow as the animal grows. The mantle continuously adds new material at the edges, expanding the shell outward. Environmental factors like water temperature, acidity, and mineral availability influence shell thickness, color, and shape.

Some species, like conchs and giant clams, produce exceptionally thick shells, while others—like angel wings—form thin, delicate structures. Despite these differences, the underlying process remains remarkably consistent across mollusks.

Patterns and Colors

Shell coloration and patterns are also mantle-driven. Pigment-producing cells in the mantle secrete compounds that embed into the shell layers, creating stripes, spots, or gradients. These designs can serve as camouflage, warning signals, or mating cues.

Beyond Mollusks

While mollusks are the primary shell-makers, other marine animals also build protective exoskeletons:

- Crustaceans (crabs, lobsters): Use chitin and calcium carbonate to form hard outer shells.

- Sea urchins and annelid worms: Create calcium-based structures called tests or tubes.

Shells are more than nature’s jewelry—they’re living records of biology, chemistry, and environmental adaptation. We study seashells to learn about efficient and durrable material composition for human use at institutions like Rice University, Princeton and USC. Next time you pick one up, you’re holding a tiny masterpiece sculpted by time, tide, and cellular ingenuity.